Tallow’s Trending—But Science Isn’t So Sure

McDonald’s ditched it. Meatfluencers swear by it. Who’s right?

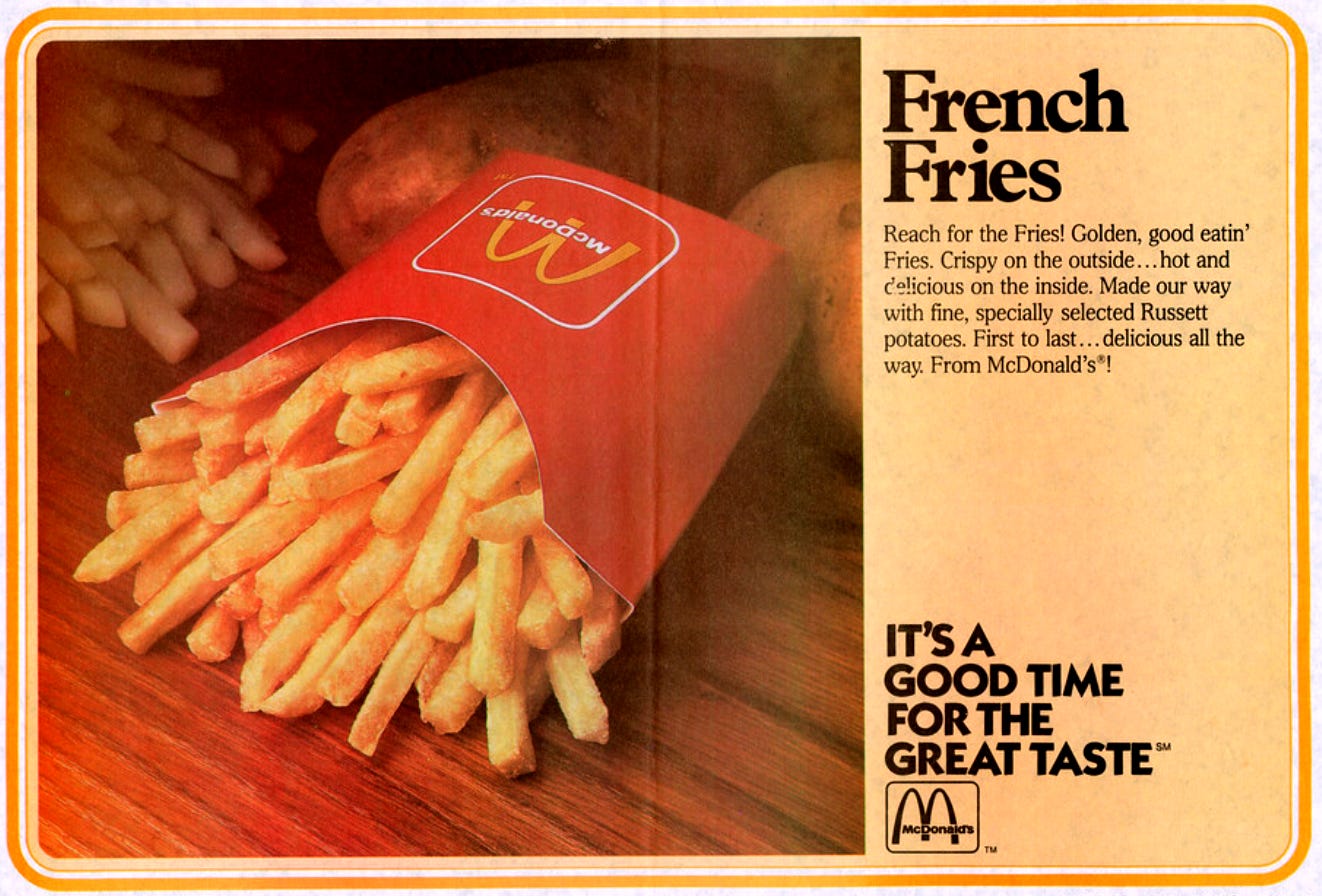

“It’s a good time for the great taste” was the iconic McDonald's tagline in the 1980s. The Golden Arches were everywhere, and their fries—crisp, golden, and deeply savory—had a cult following.

Until 1990, McDonald’s fries were cooked in a blend of 93% beef tallow and 7% cottonseed oil—giving them more saturated fat per ounce than a McDonald’s hamburger1. That year, in response to pressure from the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) and others, McDonald’s ditched beef tallow. But instead of switching to heart-healthier vegetable oils, they went with partially hydrogenated vegetable shortening—a move that introduced trans fats, which, while technically unsaturated, are just as harmful (if not worse) than saturated fats. It wasn’t until 2002 that McDonald’s finally transitioned to non-hydrogenated vegetable oils.

Fast forward to today: beef tallow is making a comeback—not in fast food chains, but in the pantries (and reels) of health influencers and others.

The same crowd that’s loudly anti–seed oil is touting a return to ancestral diets—a nostalgic (and often oversimplified) take on traditional eating patterns that include whole foods, organ meats, raw unpasteurized dairy, and, yes, animal fats like tallow. The claim? That tallow is more natural, less inflammatory, and even good for your heart.

Let’s unpack what beef tallow is—and what the science says about its health benefits.

What Is Beef Tallow?

Beef tallow is rendered fat from cows, typically from suet—the dense fat surrounding a cow’s kidneys and loins. Once rendered and refined, it becomes a solid fat that’s shelf-stable, has a high smoke point, and carries a neutral to savory flavor ideal for frying, searing, or crisping up potatoes.

Why Are People Saying It’s Healthy?

Tallow is made up of both monounsaturated fats and saturated fats, including one you'll probably hear a lot more about soon: stearic acid. Why? Because stearic acid is a type of saturated fat that appears to have a more neutral effect on LDL (bad) cholesterol compared to its more troublesome saturated siblings. Think of it as the mellow middle child of the saturated fat family—less drama, lower cholesterol impact.

Supporters of tallow like to rattle off this list of benefits:

Minimally processed and free of industrial additives

High in “healthy” fats

Anti-inflammatory

Supportive of hormone balance and brain health

For many, tallow is a symbol of rebellion—a counterpunch to ultra-processed foods and the rise of seed oils, which are often painted as public enemy number one in the world of “ancestral” eating. (I debunked many of the claims against seed oils in a prior post.)

But here’s the real question:

Do these claims about tallow hold up when we actually look at the science—or are we just swapping one fat myth for another?

What Does the Science Say?

The big picture:

Let’s start with what we do know: A high intake of saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). That’s not a fringe opinion—it’s been supported by decades of research, including large cohort studies and meta-analyses.

Zooming in:

Now, here’s where things get more interesting: not all saturated fats behave the same once they’re inside your body. They’re not a monolith, even if they often get treated like one.

Take stearic acid—the saturated fat that beef tallow fans love to name-drop. It’s found in both tallow and dairy fat and tends to have a neutral effect on LDL cholesterol, which is why it’s earned a bit of a “good guy” reputation in fat circles.

But—and this is a big but—stearic acid isn’t the main saturated fat in tallow. That honor goes to palmitic acid, which is more like the troublemaker of the group. Why? Because it’s been shown to:

Raise LDL (bad) cholesterol

Promote inflammation

So yes, one piece of tallow’s fat profile looks fairly benign, but the rest of the package is a little more...complicated. Kind of like saying a brownie has fiber because there’s a walnut in it—it doesn’t change what you’re biting into.

What the Latest Research Tells Us

If you're swapping butter for jelly on your bagel thinking you’ve made a heart-healthy choice—think again. You’ve just traded saturated fat for a hit of refined carbs, which, as it turns out, isn’t much of an upgrade. It’s like replacing your morning cigarette with a shot of vodka—not exactly a win.

Research from the American Heart Association and Harvard’s School of Public Health consistently shows that replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates (think white bread, sugary spreads, or ultra-processed snacks) can increase your risk of cardiovascular disease.

What matters isn’t just what you’re cutting out—it’s what you’re putting in its place.

When saturated fats are replaced with unsaturated fats—like those found in olive oil, nuts, seeds, and avocados—you don’t just improve heart health, you also support better insulin sensitivity and reduce chronic inflammation. That’s the kind of trade-up your body actually notices.

And the evidence keeps stacking up. A 2023 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that people with higher intakes of plant-based oils had a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared to those who leaned on butter and animal fats like tallow.

In other words: swapping beef tallow for olive or avocado oil might not just be better for your arteries—it could actually help you live longer.

Tune out the noise.

When it comes to choosing fats and oils—whether you're cooking at home or ordering takeout—it’s not about demonizing one oil and worshipping another. It’s about zooming out and seeing the big picture. Here's how to keep it simple, smart, and sanity-saving:

Make olive oil your default. It's one of the most researched oils on the planet—heart-healthy, antioxidant-rich, and endlessly versatile. For high-heat cooking, avocado oil also holds up beautifully.

Need a neutral oil? Grapeseed or canola oil do the trick—just keep them in moderation.

Want flavor? Toasted sesame oil and walnut oil can level up stir-fries, salads, or roasted veggies.

Avoid pushing oils past their smoke point (usually 400°F+). Burnt oil = broken-down fats = not ideal for your body or your kitchen air quality.

Don’t lose sleep over the occasional fried food. One French fry or a piece of fried chicken isn’t going to derail your health. It’s what you do most of the time that counts.

What You Swap In Matters

Here’s a nuance that often gets lost: nutrition is all about trade-offs. When you reduce one nutrient, you're usually increasing another—intentionally or not.

Let’s say you hold the scrambled eggs at breakfast and grab a blueberry muffin. You’ve cut the fat, but you’ve also loaded up on refined carbs and sugar—and lost the protein and nutrients that keep you full.

Smart swaps are key. Prioritize unsaturated fats, like those from olive oil, nuts, seeds, and avocado. Build meals around whole, minimally processed foods, and stay aware of the context—not just the macros.

Back to Beef Tallow…

Beef tallow isn’t evil—but it doesn’t wear a health halo either. Like all fats, its impact depends on how much you’re using, how often, and what the rest of your diet looks like. The goal is to build a way of eating that supports long-term health. That means emphasizing a balanced diet, rich in unsaturated fats and whole foods.

What About the Planet?

Tallow might seem sustainable because it’s a byproduct of meat production—but let’s zoom out. Cattle farming is:

Resource-intensive (requires tons of water and feed)

A significant methane emitter

So while using all parts of the animal is better than wasting them, relying heavily on tallow as a go-to cooking fat isn't exactly a win for the planet.

As written in Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal by Eric Schlosser, 2001, page 120

Thanks for info always great to read your articles.