Grill Marks or Warning Signs?

Heterocyclic amines, charred meat, and what the science really says about cancer risk

It’s not lost on me that I wrote a grilling cookbook and never addressed the issues I’m raising here. My work has always had two sides—culinary and nutrition—and for a long time, I kept them separate. Maybe I didn’t think they could speak the same language, or perhaps I hadn’t figured out how to let them. But if we want to live deliciously healthful lives, those conversations have to coexist. This post is part of my broader effort to bring them together—and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the divide.

One of my favorite food memories takes place at a tiny, eight-seat yakitori bar tucked away in Kyoto, Japan. The restaurant—Sumiyakisosaitoriya Hitomi—had a couple of tables, but I was lucky enough to snag the best seat in the house: dead center at the bar, directly across from the chef and his glowing binchotan grill. It felt like theater, with the chef starring as both director and performer. Every movement was deliberate, almost meditative, as he rotated skewers of chicken, vegetables, and rice balls with obsessive precision.

Then I noticed something odd. With the smallest pair of scissors, he began meticulously snipping off the tiniest flecks of char from the chicken—especially the breast meat. The vegetables? Left alone. But the chicken had to be pristine.

As someone who believes Louis Camille Maillard1 deserved a Nobel Prize for his contributions to flavor chemistry, I silently mourned every crispy, caramelized morsel that fell to the floor. Still, I didn’t say a word. Between the language barrier and my deep respect for his technique, I simply watched. And ate. Gleefully.

That memory sat quietly in my brain until years later, while I was back in the lab at NYU teaching a food science class. We were preparing meats using dry-heat methods—broiling, searing, sautéing—when a student hesitated to brown his chicken. I encouraged him to aim for a deeper sear, invoking Maillard’s legacy: higher heat, richer flavor. He considered my advice and gently pushed back: “I prefer it this way. It’s healthier.”

We’ve come to revere the char—that crispy, smoky layer that forms on grilled meats—as a flavor jackpot. But is it also a health hazard?

Here are four questions that will guide you to the answer.

First, let’s get the terms straight: Maillard Reaction vs. Char

Browning and blackening are not the same thing. One builds flavor. The other is just burnt.

Browning is thanks to the Maillard reaction—a mouthwatering bit of chemistry that kicks in when proteins and sugars meet heat (around 280–330°F). It’s how you get that golden crust on a steak or the toasty edge of a grilled cheese. The result? Molecules that taste like someone knows how to cook.

Charring, on the other hand, means you’ve crossed the line into carbonization. At this point—typically above 400°F—you’re not just cooking anymore, you’re burning. And when meat is involved, that char isn’t just bitter—it can also produce heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), both of which have been flagged as potential carcinogens. More on those in a bit.

We crave Maillard magic because it signals transformation—raw to cooked, bland to delicious. That’s why a pale boiled chicken breast tastes flat, while a grilled one—streaked with golden brown marks—tastes far richer. But push it too far, and the line between “deeply savory” and “possibly sketchy” gets thin, fast.

What Are HCAs & PAHs? And should I worry about them?

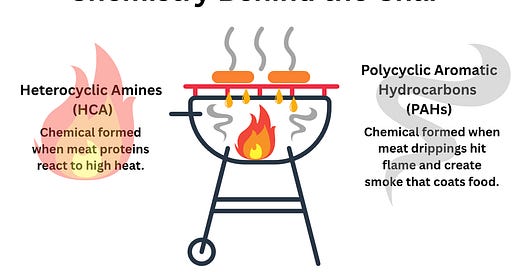

Let’s get into the chemistry behind the char.

Heterocyclic amines (HCAs)) form when meat, poultry, or fish is cooked at high temperatures—think grilling, pan-searing, or broiling. It’s a chemical chain reaction involving:

Amino acids (from protein)

Creatine (a compound found in muscle)

High heat (especially above 300°F)

When those three meet on a sizzling surface, HCAs are born. You won’t find these compounds in significant amounts in veggies, fruit, or tofu. They’re mostly a high-heat, meat-only affair.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), on the other hand, come from what’s happening around the meat. When fat or juices drip onto flames or hot coals, they create smoke—and that smoke contains PAHs. As it wafts up, it can coat the surface of your food. This makes PAHs more of a surface issue than an internal one.

And PAHs aren’t just a grilling story. They also show up in other smoked foods (like smoked cheese or salmon), and even outside the kitchen—in cigarette smoke, wood-burning stoves, and car exhaust.

What Are the Health Concerns?

In lab studies—mostly in animals—both HCAs and PAHs have been shown to damage DNA in ways that could raise cancer risk. These compounds are considered mutagenic, meaning they can cause changes in genetic material.

But before you cancel your cookout, here’s the context: the levels tested in these studies are often much higher than what you'd get from an occasional grilled steak. Human research is still evolving, and the real-world risk is likely tied to how often you eat grilled or smoked meats, how well-done they are, and how you cook them.

Translation: it’s not about strict avoidance—it’s about frequency and technique.

So, Should I Avoid Grilling This Summer?

No need to skip the grill entirely—just grill smarter.

The foods most likely to form HCAs and PAHs are muscle meats like beef, pork, poultry, and lamb—especially when they’re cooked over high heat until well-done or charred. The more fat that drips onto the flame, the more smoke, and the more potential for PAHs.

That said, there are plenty of safer—and still delicious—options:

Go lean. Choose cuts with less fat, which are less likely to cause flare-ups. Try top sirloin, pork tenderloin, chicken breasts, or skinless chicken thighs.

Embrace seafood. Shrimp, scallops, and fish fillets or steaks that cook quickly and don’t need high heat, making them less likely to form HCAs. (I love grilling tuna or salmon and purposefully undercook them to barely past rare.)

Make vegetables the star. Veggies don’t produce HCAs, and while they can pick up some PAHs from smoke, the levels are minimal—especially compared to meat. Plus, they thrive on the grill.

I need specifics! How should I grill?

Here’s how to keep grilling fun—and a little lighter on the chemical side:

Trim the fat. Less fat means fewer drips and flare-ups, which means fewer PAHs. Easy win.

Load up on vegetables. Grilling brings out the sweetness and depth in all kinds of produce. Beyond the usual corn and onions, try carrots, broccolini, asparagus, zucchini, eggplant, split romaine hearts, endive, or radicchio for a charred, caramelized edge that’s packed with flavor. Just brush them lightly with oil and season before grilling.

Avoid direct flames and flare-ups. Set up a two-zone grill if you can (hot side + cooler side) and keep a spray bottle of water nearby to tame flare-ups as they happen. You want heat—not fire.

Marinate when possible. Some solid science backs up marinating: a study in the Journal of Food Science found that spice-rich marinades containing rosemary and thyme slashed HCA formation in grilled beef by up to 88%, thanks to antioxidants like carnosic and rosmarinic acid. And if you can get sturdy rosemary springs? Use them! They’re not just for show—they make excellent natural basting brushes and deliver extra antioxidant power right where it counts on charred meat.

Grilling isn’t the villain—it’s the method that makes the difference. High temps, fatty cuts, and open flames set the stage for compounds like HCAs and PAHs. But with a few smart swaps, you can keep the flavor and skip the sketchy health concerns.

Think of it like skincare: sun exposure isn’t the problem—unprotected, repeated overexposure is. You don’t need to hide indoors; you just need a good routine.

So: trim the fat, control the flame, load up on vegetables, and go lean when it comes to meat. The grill’s not the problem—it’s how you handle the heat that matters.

Louis-Camille Maillard was a French chemist who, in the early 1900s, discovered the chemical reaction between amino acids and sugars that gives browned foods their flavor and color. This process, now called the Maillard reaction, is key to the taste of grilled meat, toasted bread, and roasted coffee.