Welcome to Fed—I’m thrilled you’re here! This is your go-to resource for nutrition questions and controversies. Think of me as your tutor—here to break down the noise, offer context, and help make sense of it all.

For my first post, let’s talk about something that fuels a lot of nutrition debates—research. I hear it all the time: Why does nutrition advice keep changing? One day, eggs are the enemy; the next, they’re a superfood. Whole milk? Same story. I get it. How hard can it be to figure out if an egg is detrimental to your health?

Well… turns out, pretty hard. Or rather—it’s not exactly easy.

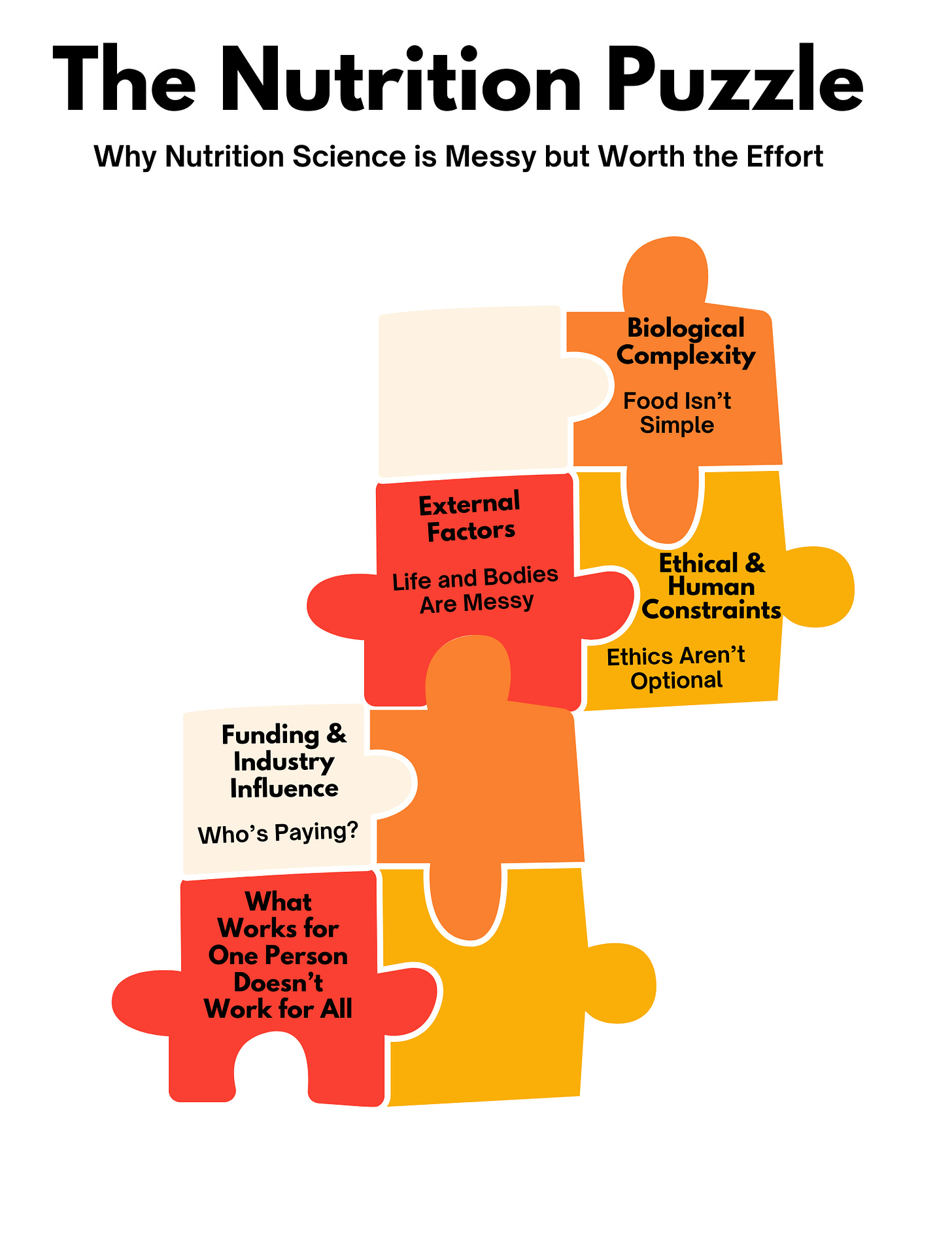

Nutrition research is complicated

I hear a lot of people say, “Do your research!”—which is well-intended but way easier said than done. Before you go down that rabbit hole, let’s get one thing straight: real research isn’t just a few quick Google searches. Understanding nutrition science is key to making sense of it.

First off, it moves at a snail’s pace—because studying food and health is absurdly complicated. You can’t lock people in a lab, make them eat only eggs, and control every single factor that affects their health (and let’s be real, no one would sign up for that). Even if you could, no two bodies react the same—genes, stress, sleep, and even gut bacteria all throw curveballs into the mix.

And here’s where things get tricky: bias. Some studies are funded by industries that have a stake in the results (hello, food and pharma companies). Others suffer from researcher bias, poor methodology, or cherry-picked data. That’s why one study—even if it’s well-designed—is never the final word. Science isn’t about quick answers; it’s about patterns that emerge over many studies, replicated across diverse groups of people.

So if someone says, "I’ve done my research, and here’s the truth," take it with a grain of salt. Science is a puzzle, and we’re still piecing it together. Good research takes time, and when it comes to nutrition, anything that sounds too certain is worth questioning. That said, some truths do hold up—like eating your veggies and keeping your calorie intake in check. Not the flashiest advice, but the boring stuff is often the most reliable.

Ok, so how do I know who to trust?

Great question! Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer—but I can give you a solid starting point. Below are some of my go-to sources for nutrition research, plus a few key things I consider when deciding whether advice is worth listening to.

Primary Sources

These give you direct access to the research itself. The downside? You have to do the work of interpreting the findings and assessing their quality.

NYU Libraries – This is where I do most of my research, but I know not everyone has access to a university library. A couple of great public options:

PubMed – A solid database for peer-reviewed studies.

Google Scholar – Another good tool, though it often only provides abstracts (which is a good start, but you may need full studies for deeper insight).

Semantic Scholar – A free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature. You enter a keyword, and it pulls up a list of related studies. It’s great for filtering through research, but you’ll still need to sift through results. For example, searching “food dyes” gave me 2.1 million results here, compared to 3.1 million on Google Scholar—so it’s a useful tool but requires some patience.

Secondary Sources

These take research and translate it into digestible takeaways. They’re convenient and often reliable—but they can also be biased. Here are a few I trust for balanced, well-researched nutrition content:

New York Times Well Section (especially articles by Dani Blum and Alice Callahan)

Sigma Nutrition (podcast & website)

Harvard School of Public Health - The Nutrition Source

How I Vet Other Sources

There are dozens more good sources beyond my go-to list, and I often read from other places too. When I do, I turn on my BS monitor and run through this checklist:

✅ Who’s behind it? I check the author’s credentials (yes, they matter!), see if they’re being paid for their opinion (funding bias is real), and look at their overall body of work—are they respected in their field? What other views have they held? What projects have they been involved with?

✅ Are they citing actual research? Do they reference primary research, or are they making broad claims with no citations—or worse, just saying “research shows” without backing it up?

✅ If they cite research, is it solid? I cross-check it against my evidence ladder to determine its quality and relevance.

No single source is perfect, but these steps help separate solid science from sensationalism. The key is to stay curious, think critically, and always follow the evidence!

I'd love to know what you're curious about. Send me your questions or a topic you'd love more info on in the comment box below—I’ll use it as inspiration for a future post!

Top 5 reasons nutrition research is complicated

#1

#2

#3

#4

#5

.